Misinformation about children being abducted by social services is a familiar phenomenon in most Nordic countries, but the fact that it is a phenomenon with regional variations, has not been well known – until now.

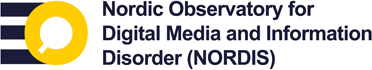

In April 2022, a video containing Arabic language allegations that Finnish social services kidnap children in order to sell them for profit was published on YouTube.

«They take the child and then they trade the child. Not to take care of the child and move him to a better family, but for money», the video claims.

«When a social worker sees you with your happy and healthy children, she plans to stage a situation where she can abduct them. Social workers take the child and make a profit of 1000 euros a day.»

The video also claims falsely that in Finland, social services are taking children from immigrant parents for use in drug tests, sex trafficking, and other forms of exploitation.

The account behind the video, Shuoun Islamiya, which is run by the Egyptian blogger Mustafa Al-Sharqawi, had previously published similar accusations against Swedish welfare agencies.

Faktabaari was the first media outlet in Finland to report on the propaganda against child protection spreading in Arabic-speaking communities in Finland. Faktabaari became aware of the issue through NORDIS cooperation.

Mervi Pantti, Professor of Media and Communication Studies at the University of Helsinki, and part of the NORDIS research team explains that the misinformation campaign should not be viewed as linked to child protective services as such:

– Child protective services are just a perfect victim to enlist in service to a bigger political goal, because stories like these about child protective services can generate very strong feelings of injustice, discrimination, and hatred towards authorities, Pantti says.

An initial campaign against Sweden

While the existence of disinformation targeting child protective services is well known in most Nordic countries, the fact that similar kinds of misinformation are common in the entire region is less well known. Now, a collaboration between NORDIS fact-checking partners Faktabaari, Faktisk.no, Källkritikbyrån, and TjekDet has uncovered connections – and dissimilarities – between the content and target groups of this type of misinformation across the Nordics.

Indeed, the video about Finland was not the first time Al-Sharqawi targeted a Nordic country. Just a few months earlier, the Swedish Psychological Defense Agency noticed a campaign against Swedish social services run by none other than Shuoun Islamiya.

Al-Sharqawi’s disinformation effort targeting Sweden delivered the blueprint for the subsequent campaign against Finland.

In the middle of January 2022, false claims of systematic child trafficking by the social services in Sweden saw coordinated amplification on Twitter, where the allegations were coupled with threats of violence and terrorism.

Shuoun Islamiya has maintained its focus on Sweden since launching the campaign last January:

Ahead of Shuoun Islamiya’s campaign, social media posts about cases where children were taken from their parents by child protective services had attracted the attention of Muslim immigrants.

Doku, an investigative journalism website, reported that these posts commonly misdescribed the treatment these children received. The posts, claimed, inaccurately, that Muslim children were forced to convert to Christianity, eat pork, drink alcohol, and that Muslim girls were raped and forced to remove their veils.

Attacks on same-sex couple

Later, in the fall of 2022, the Swedish influencer couple, John and Johan Valencia, published the book Miriam and the Magical Sweater, inspired by their own family: a gay couple with two adopted daughters.

Following the book’s publication, Shuoun Islamiya creator Mustafa Al-Sharqawi attacked the Valencias. In one video, Al-Sharqawi claimed that Sweden had kidnapped a child and given it to a gay couple while stating, falsely, that «Miriam», the name of the book’s titular character, is a Muslim name.

The video received tens of thousands of views, and a large number of commenters expressed hateful and anti-gay sentiments toward the Valencia family. At one point, Aktarr, an Arabic news outlet based in the Swedish city Malmö, published an article containing these false claims.

– We saw this repeated in major channels and failed in our fact-checking. We will post a correction and are really sorry about what has happened, Aktarr editor Kotada Yonus said to the Swedish newspaper Sydsvenskan when confronted with the inaccuracies in the story.

As a result of the untrue news stories based on Al-Sharqawi’s false allegations, John and Johan Valencia received hundreds of hateful messages and threats.

– It hurts, partly because it was untrue and because it’s hard to handle false accusations, but also because this is about the safety and security of our family and our daughter, John Valencia said to the Swedish public broadcaster SVT.

NORDIS partner Källkritikbyrån has not received responses on requests for comments from Mustafa Al-Sharqawi or Aktarr.

«You either take your children back or die a martyr»

In online groups devoted to criticism and, in some cases, hatred against social services, the conversations occasionally turn into threats of violence, even terrorism. One member in the Facebook group «Familjens frihet» posted a TikTok video from mid-January claiming «the Swedish state kidnaps our children to make money».

In another Facebook group, «Barnens rätt », a member posted an article about a bomb threat against the local social services office in the city of Skara. Another member responded by writing «Good, that’s what they deserve».

Not everyone falls for the disinformation and some have even changed their minds along the way. One father who started campaigning against social services in Sweden told Mustafa Al-Sharqawi in an interview in December 2021 that the Swedish social services kidnap children.

Now, more than a year later, the father has had a change of heart and is planning a new organization, to help parents in their interactions with officials, but also to oppose conspiracy theories.

– I started a disinformation campaign. Now I am starting an anti-disinformation campaign, he told the Swedish newspaper Svenska Dagbladet.

The perfect target

Research suggests that dis- and misinformation, unfortunately, spread faster and wider than factual or truthful stories. According to Mervi Pantti, the disinformation by Al-Sharqawi illustrates why:

– Child protective services are such an emotional and intimate field. It involves both small children and our homes where authorities intrude and take the most precious thing you have, she says.

This makes child protective services the perfect target for people like Mustafa Al-Sharqawi and others who want to create distrust of authorities, a common goal for spreaders of disinformation.

Pantti points to a video from Sweden as an example:

– You can see the anger element in the message itself, and it’s even visualized anger where parents are crying and screaming that they have not seen their children. And in addition to this, there is anger in the replies on social media, which also contributes to the spread, she argues.

Imported by Hizb Ut-Tahrir to Denmark

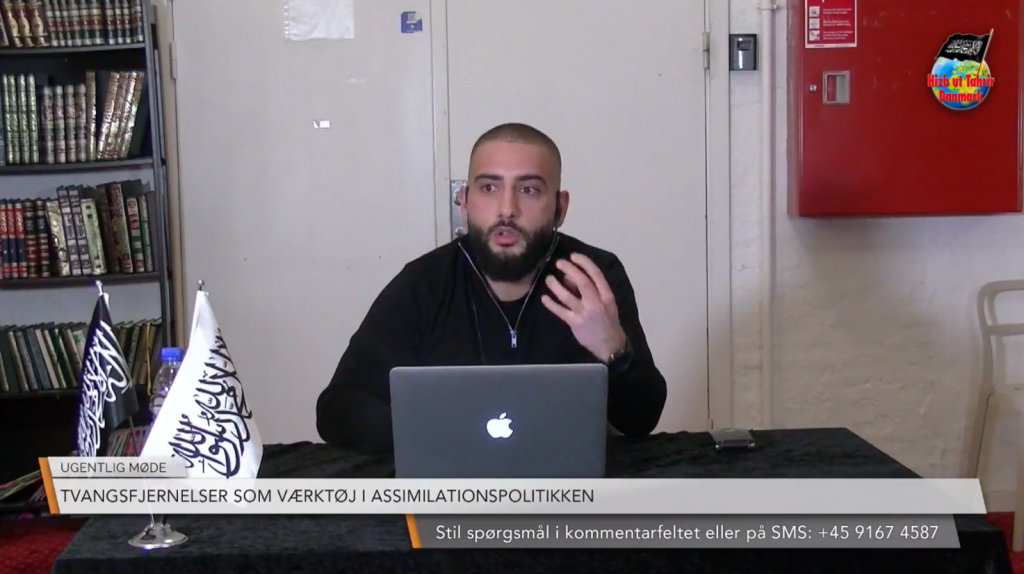

While Denmark was not a direct target of Shuoun Islamiya’s disinformation campaigns, the Islamist group Hizb Ut-Tahrir made an attempt to adapt elements of the campaign to their local context and agenda in early 2022, when the disinformation campaign against child protective services in Sweden was at its most intensive.

In February, the organization held a virtual meeting focusing on forced removals of Muslim children, titled «Forced removals as a tool in assimilation policy». A Hizb-Ut-Tahrir spokesperson criticized the Swedish authorities.

In a video recording of the meeting, the Hizb-Ut-Tahrir spokesperson claims, falsely, that forced removals of Muslim children are part of Danish assimilation policy and that those who deal with forced removals and adoptions are trained to consider the extent to which Islamic values are adopted in a household when assessing whether or not a child should be removed from its parents.

Later in the meeting, the spokesperson claims that authorities’ focus on Muslims entails that they are particularly happy to remove children from Muslim families. A group of women associated with Hizb Ut-Tahrir-linked also repeated the criticism in a Danish-language post on their Facebook page.

In fact, Danish authorities are not allowed to record the religious affiliation of its citizens. Hence, it is not possible to provide exact figures about the number of Muslim children being removed from their parents.

Nonetheless, a 2021 analysis from the former Ministry of Social Affairs and Senior Citizens, based on figures from 2019, provides figures for reports and removals divided by ethnicity. As TjekDet has reported, these figures do not prove that authorities in Denmark are more prone to removing children and young people from the MENAP region and Turkey, which are countries where the majority of the population are Muslims.

We reached out for a comment from both the spokesperson in the video and Hizb Ut-Tahrir, but they have not responded to our requests.

In an earlier article by TjekDet the spokesperson concedes that Islamic values does not officially appear as a criterion for child cases and forced removals but insists that Islamic values is a criterion indirectly.

«This is not only due to a cultural bias of the individual caseworker, but a thorough politicization of the field of ‘parenting’ and combating what is called ‘social control’, ‘honour-related conflicts’ as well as ‘radicalization’ and ‘extremism’. These are strongly politicized concepts that in reality include common Muslim norms, values and identity formation,» he said.

According to the spokesperson, it is not the number of removals that determines whether forced removals is a political tool in Denmark.

In Norway, large groups gather parents opposed to «Barnevernet»

While Norway largely escaped Shuoun Islamiya’s campaign, the country’s experiences nonetheless show how child protective services are an ideal target for misinformation, but also that the practices of child protective services in the country have been subject to legal challenges – some of them lost – in the European Court of Human Rights.

Grievances against Norwegian child protection began growing as early as 2011, when an Indian couple in Stavanger were deprived of their two children. In the next few years, thousands of demonstrators around the world took to the streets to protest against Norwegian child protection, and the Norwegian word «Barnevernet», the local term for child protective services, became a swear word in several languages.

In 2012, supporters of the Indian couple organized a protest in New Delhi. The case has since become the subject of a Bollywood film. In 2016, protests against «Barnevernet» were organized in 20 countries, including Poland, Romania, and the UK. Previously, then Czech president Milos Zeman had compared Norwegian child protective services to the National Socialist lebensborn program.

In the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, Norway has been convicted of human rights violations in 15 child protection cases to date.

Today, groups opposed to child protective services are growing on social media in Norway. Parents experiencing life crises seek help in groups characterized by users exposing personal information, as well as polarization, power struggles, and misconceptions of the facts. Conspiracy theories about how the system works are common, as are incitement and threats against public servants.

There are at least 25 Norwegian groups, pages, and personal profiles that have the same goal: To radically change Norwegian child protection services. However, the claims made in the groups do not differ substantially between the ethnic or religious backgrounds of the members.

Not (just) misinformation

In Norway, unlike in Sweden and Denmark, the most common claims in these groups are not necessarily false and often linked to already existing critiques of the Norwegian childcare system.

The smallest groups only have a few hundred followers, while the largest is followed by almost 25 000, according to a recent review conducted by Faktisk.no and the daily newspaper VG. The largest groups are public, so everyone can see what is shared in them. Other groups require membership.

In total, the groups, pages, and profiles have over 140 000 followers. However, due to overlapping members, the true follower count is likely lower.

In a series of articles and fact checks about «Barnevernet», published in the latter part of 2022, Faktisk.no investigated some of the most widespread claims in these groups. Here are some examples:

Child Protective Services steals children

Technically, this claim is not the easiest to fact-check. What does it mean that the CPS «steals children»? However, it is possible to make some facts clear. Looking only at the number of times children are taken into custody by the CPS, one can discern a decreasing trend: from 1516 in 2018 to 981 in 2021. About half of these children are subsequently returned to their parents.

Child Protective Services steals children for profit

A more specific version of this claim is similar to one that was circulated by Shuoun Islamiya: that the CPS «steals children for profit».

Like in Finland, this claim was taken from a 2015 news story by national public broadcaster NRK, according to which some foster parents receive up to 60 000 NOK monthly from the CPS. Of course, this is far from being evidence for the claim that the CPS «steals children for profit».

The Norwegian Child Protective Services takes more children from their biological parents than any other comparable country, and placements in Norway are more often forced.

This claim is closely linked to the fact that Norway has been convicted by the European Court of Human Rights for violations in 15 child protection cases.

This claim is false. Statistically, Norway ranks close to Denmark and Germany. The Norwegian CPS conducts fewer placements than Sweden and Finland, but more than the USA and England.

According to Marit Skivenes, who researches the Norwegian child protection system, it is also incorrect that the Norwegian placements take place by force to a greater extent than in countries like Denmark, Sweden, and Finland:

– In the Norwegian system, all care takeovers that have come before the courts are defined as coercive decisions, even if the parents consent.

Misinformation adapts

When asked about the different forms of misinformation about child protective services in the Nordic countries, Åsa Wikforss, professor of philosophy and a prolific theorist of misinformation and fake news at the University of Stockholm, points out that propaganda and misinformation are highly adaptive:

– The way propaganda works is that you look at the local situation and you identify what can be exploited here. The possibilities for exploitation will be different from country to country, she says.

– In Norway, it seems more like the misinformation about Barnevernet is reaching people who are less driven by those kinds of cultural value differences, and I think that it is not a coincidence. In Sweden, you could exploit these differences much more than you could in Norway because the level of immigration hasn’t been as high in Norway. But it is presumably also spread towards people with low trust in the institutions in Norway, Wikforss says, adding that she thinks that misinformation about child protective services exploits and deepens already existing societal divisions.

Distorts an actual news story

Campaigns against child protective services often rely on misrepresentations of ordinary news stories. For example, the Shuoun Islamiya video about Finland relies on an investigation of Finnish orphanages to bolster its claims about trafficking and exploitation.

The story, which was published by the Finnish tabloid newspaper Iltalehti, is about the rising costs of foster care in Finland, where municipalities, in some cases, have paid care institutions up to 1000 euros per day for a single child.

However, contrary to the claims made in the YouTube video, the article is not about human trafficking, but about how private care institutions have made a profitable business out of running child protection institutions. So in the Youtube video, the real report has been taken out of context and used for propaganda.

A previously unreported form of misinformation

Attacks on the credibility of Finland’s child protective services are not new. In 2011, Finnish public broadcaster Yle’s Silminnäkijä programme followed Johan Bäckman, who is well known for spreading anti-Finnish propaganda, on one of his speaking tours in Russia. During his tour, Mr. Bäckman baselessly accused Finnish social services of human rights violations and called child protection «political terror».

Mr. Bäckman’s message found a ready audience in Russia, and in 2012, the Finnish government had to respond to claims of «mistreatment» of Russian families in Finland. The issue has since been raised repeatedly.

However, until Faktabaari published its story, misinformation about child protective services directed at Arabic-speaking communities in Finland has not attracted the same attention as Mr. Bäckman’s claims.

Nonetheless, some institutions and NGOs have been aware that immigrants face challenges connected to cultural differences and interpretation, and many Arabic speakers living in Finland believe that racist and prejudiced attitudes influence the decisions of government agencies.

According to Ala Saeed, a peer support planner at the Finnish Refugee Aid, an NGO, it is likely that rumours about child protection authorities have been rife in Finland, in particular between 2015 and 2020.

Neither Saeed nor migrants interviewed by Faktabaari believe that the notion that social workers would traffic in kidnapped children is common. Faktabaari’s investigations indicate that the examples that are discussed on social media are often drawn from Sweden.

Countering misinformation

There is not only one thing to do but rather a toolbox full of things to do, argues Stockholm University’s Åsa Wikforss when asked how to counter misinformation.

– If you look at the system as such, you can demand more responsibility from the tech giants. This is difficult because constant moderation is tricky. Because of freedom of speech, moderation has to be done with a certain level of care and intelligence. You can demand fact-checking efforts and make technical tweaks to slow information on social media platforms down, so things can’t be shared as quickly as now.

Wikforss also sees potential for interventions at the individual level:

– More can be done to protect people against dis- and misinformation by teaching how disinformation works, what techniques are being used, and what to watch out for, and what characterizes reliable sources, she concludes.

Editor:

Morten Langfeldt Dahlback (Faktisk.no)

Reporting by:

Daniel Greneaa Hansen (TjekDet)

Eva Akerbæk (Faktisk.no)

Nathalie Damgaard Frisch (TjekDet)

Petra Piitulainen-Ramsay (Faktabaari)

Pipsa Havula (Faktabaari)

Åsa Larsson (Källkritikbyrån)

Headline image credit: TjekDet

Additional reporting by Miriam Huovila in Finland.