The Aarhus team analysed a large dataset of tweets using specially trained model.

The text below is the report’s executive summary. A complete version of the report can be accessed here.

In February 2020, only a month after the Covid-19 pandemic was declared, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that the crisis was accompanied by an ‘infodemic’ of misinformation (WHO 2020). Whereas previous public health crisis also affected millions, constant media coverage regarding COVID-19 and extended use of social media turned this scenario into an unprecedented situation with two co-occurring but different types of crises: Covid-19 and an aggravated misinformation crisis.

When investigating crises in a context of resilient democracies, as is the case of the Nordic countries, questions around collective action arise. In particular, it has been argued that democracy poses a problem to collective action, since for every individual citizen, the cost of productive political engagement often outweighs the additional policy benefits to be gained from such behaviour.

In the case of the Nordic countries, this effect might be further strengthened by their comprehensive healthcare systems, high levels of education and high levels of trust in organizations and the media. Nevertheless, situations in which a threat arises, might break the resistance to step out of the individual comfort and motivate citizens to organise for collective action. How does that happen? A strong body of research supports the importance of emotions in that context.

In this study, we use Twitter data from the Nordic countries during the second wave of the pandemic and select tweets containing hashtags pertaining to one of each of the following categories: misinformation-related hashtags, highly used Covid-19 hashtags and highly used general hashtags.

We opted for this approach based on previous work arguing for an additional function of hashtags to act as linguistic markers indicating the target of the appraisal in the tweet, that is, who is the user addressing to with their interpretation of a situation, going beyond their organizational and topic-making function. The use of hashtags has been argued by Zapavigna to have an additional function to upscale the call to affiliate with the values – or share the emotions – expressed in the tweets, which can be further associated with states of action readiness potentially leading to collective action.

Which emotions appear more predominant in tweet appraisals referring to crises in the Nordic Welfare system?

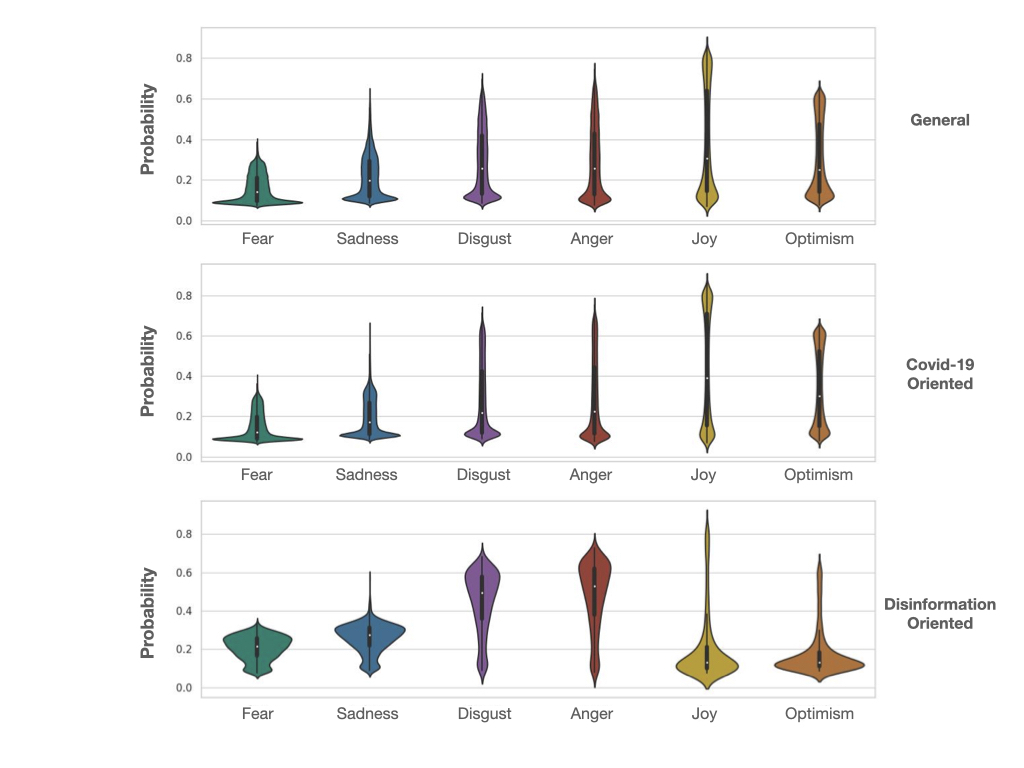

Our study shows that fear and sadness appeared consistently higher in both types of crisis appraisals (Covid-19 and misinformation) across all the Nordic countries taking part in this study. The only exception was Denmark, in which we did not find any significant differences in the amount of fear expressed in the Covid-19 vs. general appraisals. While the effect was present in both types of crisis appraisals, shown as significant results in both cases, the effect sizes were large for the comparison between misinformation and general tweet appraisals, but only small for the comparison between Covid-19 and general tweet appraisals. In other words, we do not see a large increase in the use of fear and sadness expression in appraisals that refer to the Covid-19 crisis. In relation to collective action, these two emotions often have an inhibiting effect, which – if we were to take these results in isolation – would be stronger in the misinformation crisis.

In regards to the expression of anger and disgust in appraisals, we found a significant and very large effect when comparing the misinformation vs. the general tweet appraisals in all Nordic countries. This is interesting because anger, and the related emotion disgust, are strong predictors of collective action. As such the data would indicate a very fertile context for collective action around misinformation. In the case of Covid-19 vs. general tweet appraisals, results were not as consistent across countries, and the effect size was small even in cases where significant differences were present. In particular, only Swedish and Norwegian tweets had higher expression of anger and disgust in Covid-19 tweet appraisals, whereas the oppositive effect was found for Danish and Finnish tweets. As such, we would expect anger to act as a potential driving force for collective action only in the misinformation crisis. However, the accompanying high expression of fear and sadness might play an attenuating effect.

Before diving into the interaction of anger, fear and sadness, and the potential for collective action when taken into combination, it is worth mentioning that the presence of joy and optimism was consistently higher in the non-crisis appraisals, both Covid-19 and misinformation appraisals. However, as with the case of negative emotions, the effect sizes were much larger when comparing misinformation vs. general appraisals than when comparing Covid-19 vs. general appraisals, indicating that the emotional landscape of misinformation appraisal tweets differs strongly from the general emotional landscape in all its components.

How do anger, fear and sadness interact in crisis appraisals?

Given the importance of the interaction between negative emotions for collective action, we further investigated the relationship between all pairs of negative emotion expression: Anger-fear, anger-sadness and sadness-fear. In theory, collective action can be facilitated by high levels of anger and low levels of fear and sadness. As such, a change in the ratio between anger and the other two emotions, where fear and sadness become more prominent, might indicate decreased chances for collective action. This is what we found in the Covid-19 vs. general tweet appraisals. On the other hand, a change in the ratio in which fear and sadness become less prominent, leaving anger dominate, might lead to increased chances for collective action. We found a trend towards this effect in the misinformation vs. general appraisals. Further research is needed to investigate how this quantifies in online and offline collective action.

Overall, we found differences in emotional expression when comparing two different types of crisis oriented tweet appraisals in the Nordic Twittersphere. Taking into consideration the Nordic context, with their resilient democracies and high trust societies, emotions have been suggested to be particularly important in organising for collective action (Groenedyck, 2011). This study suggests that the misinformation crisis would be more likely to present a fertile environment for collective action in the Nordic countries than the co-occurring crisis around Covid-19. However, more research is needed to investigate the degree to which this translates into collective action both in online and offline behaviour.